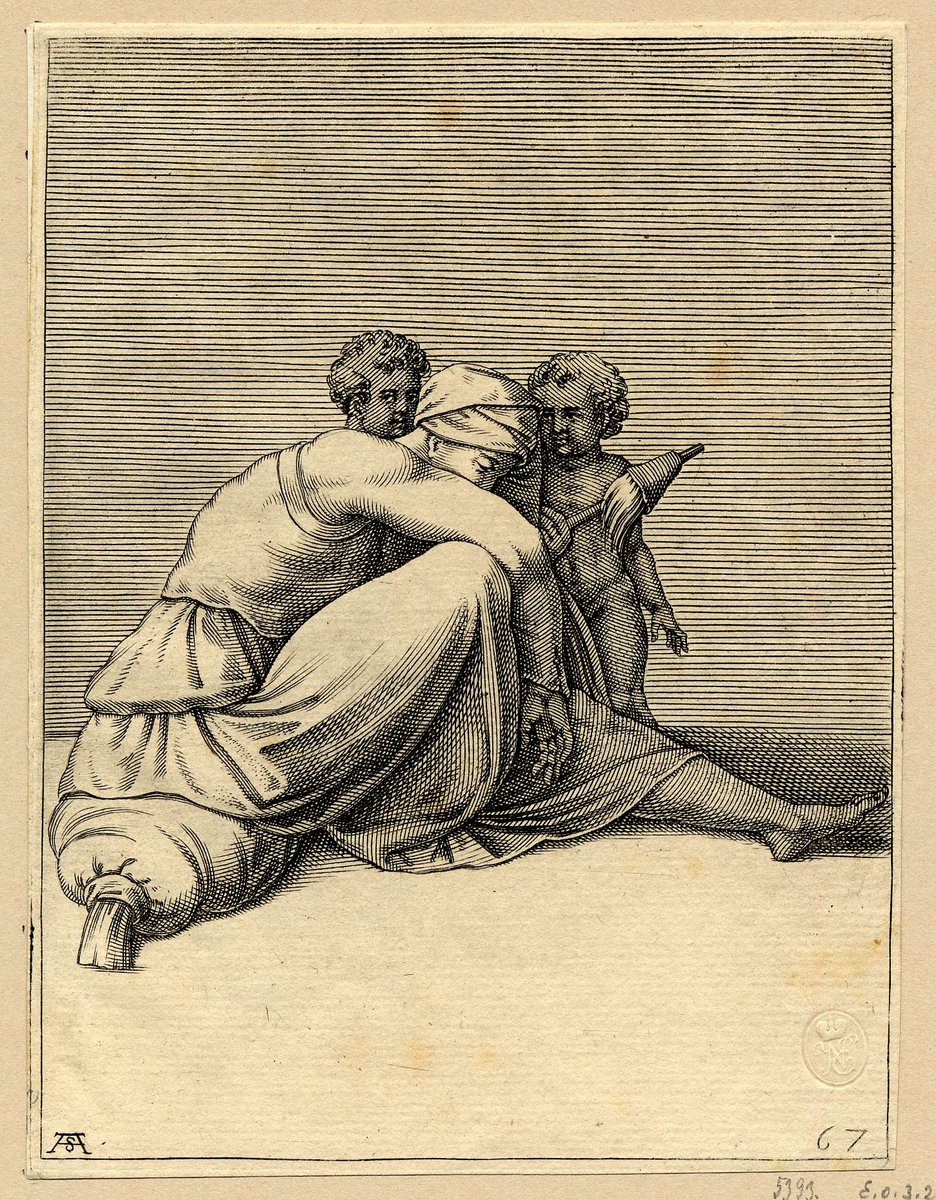

Woman with a Distaff and Two Children, Figures from Spandrel, from a Series of Seventy-two Studies after Figures of the Sistine Chapel

Prints and Drawings

| Alkotó | |

|---|---|

| Kultúra | German |

| Készítés ideje | ca. 1790 |

| Tárgytípus | drawing |

| Anyag, technika | black pen, watercolour over black pencil on paper |

| Méret | 228 × 178 mm |

| Leltári szám | 1914-143 |

| Gyűjtemény | Prints and Drawings |

| Kiállítva | Ez a műtárgy nincs kiállítva |

Born in Zurich and trained to be a preacher, Fuseli (originally Füssli), a man of extreme erudition, was one of the most influential figures of the cosmopolitan art world of the 1800s. The eight years he spent in Rome (1770 – 1778) were decisive in his becoming an artist. In 1780, he settled in London, where he was equally at home in literary and art circles. Although he was the one to translate into English Winckelmann’s influential Reflections on the Imitation of Greek Works in Painting and Sculpture, a standard work on the aesthetics of Neoclassicism, his own visionary paintings and drawings make him a representative of the pre-Romantic Sturm und Drang. A great many of his works were inspired by literary masterworks, the writings especially of Homer, Dante, Shakespeare and Milton. His vivid imagination and eccentric visions were responsible for an extremely original art, in which the borders between fantasy and reality become indistinguishable. His contemporaries were equally enthusiastic about his paintings, his theoretical writings and academic lectures.

His drawings, among which representations of his wife, Sophia Rawlins, form a distinct group, are very diverse both in subject and technique. In his late forties at the time, the painter married the exciting beauty, a professional model who was about twenty years his junior, in 1788. The artist depicted his wife in innumerable forms, views and costumes: she now appears as a kind, caring woman, then as a demonic femme fatale. Common to all the representations is that Fuseli always paid much attention to external features. This is also obvious in the drawing held in Budapest, which is a half-length portrait of the young woman, who turns towards the viewer. Her hair, stacked up and decorated with ribbons, is immediately conspicuous. Fuseli laid great store in appearance, and encouraged his wife to dress, and wear her hair, fashionably yet originally. Hair had a special, almost fetish-like, importance for him. The hairstyle and the garment also help to date the pieces: the drawing held in the Museum of Fine Arts is similar to one dated by the artist and kept in the Zurich Kunsthaus, which suggests the former was also made around 1790. The composition of the drawings is also similar: the figure of the young woman is, in both cases, sharply distinguished from the dark, brownish mass of the background; Fuseli did not find it important to hint at the environment at all. He represented the clothes with a few bold pen strokes, the hem of the skirt dissolving into nothingness. Similar is the broad black ribbon tied under the breast, which emphasises the slim waist. The three-quarter profile, the slightly bent head and the mischievous look make the model in the Zurich piece more accessible than the frontal presentation of the Budapest drawing, in which the special coiffure practically envelops the head. The fixed look and the expressionless pale face emerge from the interplay of the moderately used soft rosy and brownish tones.. The masterly combination of pen and brush, and the restrained colouring, make this piece one of the subtlest, most sensitive works of the artist.

Text: © Zsuzsa Gonda

A folyó kutatások miatt a műtárgyra vonatkozó információk változhatnak.